contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

Wolfram Richter

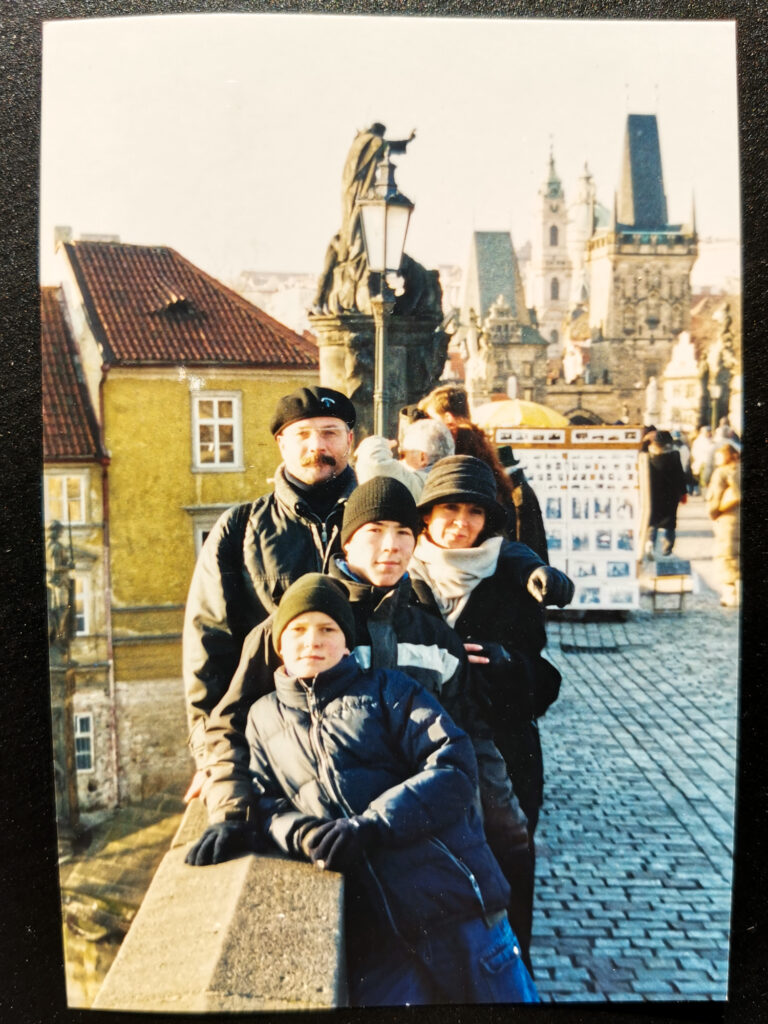

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Wolfram Richter was born in Radebeul in 1957. He grew up in Freital near Dresden and completed his A-levels there. He then studied architecture in Dresden until 1983 and worked as an architect until he left the country. Together with his pregnant wife Claudia and their three-year-old son, they wanted to leave the GDR in 1988. However, his application to leave the country was not granted and he was transferred to socialist beer production. On… he went to the Prague embassy with his brother Joachim, as he had heard that the lawyers Wolfgang Vogel and Gregor Gysi were registering those wishing to leave the country there. Wolfram Richter and his brother witnessed Genscher’s speech there, but did not want to leave their wives and children behind in the GDR. They refused to leave the country and negotiated a solution on their own, which initially led them back to the GDR. In November 1989, they were allowed to leave the country with their families.

After leaving the country, the Richter family initially moved to Hesse. Today they live in Dresden again. Wolfram Richter now teaches as a university lecturer at Coburg University of Applied Sciences.

Why did you leave the GDR?

We are both architects, we both studied architecture at the TU in Dresden. And something struck us, namely a sentence in the lecture on architectural history that said: “Here you can see St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Take a close look at the pictures in the slide, because it won’t be possible for us to go there. Or it won’t be possible for you. And immediately after this lecture, which was in 1979 or ’80, I said to myself: something is not right here. Either you wait and hope that society will change somewhere or I have to take matters into my own hands. And that then became a principle for me, to tackle all the things that don’t suit me myself, to stand up for myself. And that became a principle, despite all the thoughts and doubts I had. That we will forever reproach ourselves if we haven’t even tried. This ‘try once’ at least and if you are rejected x times, then you just have to try again and again. And then, of course, for us, for our profession of architecture, there were often situations where we were restricted [hatten] in the implementation of our plans, our ideas, our designs [eingeschränkt waren]. This impossibility [der Entfaltung], because there was no material or not the material we could have used. There was a ban on the use of steel and wood for design purposes. And these were restrictions for us, and we said to ourselves: Either I submit to this or I really have to change something now. […] Budapest was the West of the East. And there we had the opportunity to find things in interior design or architecture magazines that were different. Things that corresponded to our dreams, our wishes, but were not possible to realize in the GDR.

And then the whole thing matures. […] It was a maturing process that eventually brought the barrel to overflowing. […] We realized that things weren’t human here, that it was all about political reasons and anyone who didn’t fit in with this regime had to leave. I realized that when I worked as a project engineer at TU-Projekt, [so] was the name of the company at the time. I was responsible for the planning of two new lecture halls at Zittau University. At the time, [als wir] applied to leave the country [hatten], I was appointed director the next day and was relieved of my duties. And then they said, please go, it was a Friday, please go and work in socialist beer production here in one of the Dresden breweries from Monday. Those were the reactions that the state or this society had in store for us, and it was clear to us that we had eaten our fill. We had dropped our pants and made ourselves known, which meant we had zero chance in society.

[Zu den Repressalien der Stasi]

We went on vacation, but at the same time we had heard that apartments were being searched while people were away for long periods of time. So I came up with some kind of security to check [ob] whether someone was in our apartment or not. [Bei dem] The idea that someone would break into your apartment and then basically find evidence to present to [sie] you when you were arrested, we knew we had to take action ourselves, otherwise they really would get us off the stage. Because there were so many actions. I knew, you have to imagine, my phone was being tapped. I was employed at the TU, talking to a friend on the phone and suddenly it goes chrt-chrt-chrt and a voice says: Please leave this call, it’s a TU Dresden office phone. I say: Hello, are you still there? Hello, Elke, is that you? Are you joking now? Leave this call! And that made me realize that someone was listening in. And the following week, a blue man came into our office and said: Please everyone out, we need to check the technology here. That seemed Spanish to me, so I went outside, but I came back a minute later and he was standing right by my phone, everything disassembled, and I said: What are you doing here? Yes, your phone is incredibly dirty, it needs to be cleaned first. So he fitted me with a new bug or something. I knew my phone had been tapped, so what did I do? In the end, because things weren’t going any further with our departure [ist], I started telling political jokes on the phone. In 1986, a law was passed in the GDR [veröffentlicht] that meant you could be arrested for telling political jokes. […] At the time, I thought to myself, now I’m doing it consciously. I accepted the fact that I would be sentenced, that I would go to prison and that I would then basically be released [in den Westen komme]. And that’s another point: a fellow student of ours had also applied to leave the country, [der] was also constantly rejected. And he did it like this: it was common at the time to have a wedding ribbon on your car antenna. That was a sign that you weren’t from the registry office, but that you were applying to leave the country. Or you would put a ribbon in the back of the parcel shelf of your car and it would say ‘Wir sind Ausreiseantragsteller’ in big letters. After all, you could put whatever you wanted in your car. And that was enough. He did that and they picked him up from work early in the morning, from the office. He went on trial at lunchtime and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, of which he actually served one and a half years. He later told me that he had been in the same cell as murderers. And then he was ransomed in Berlin at the famous Glienicke Bridge, where this prisoner exchange always took place.

Let's move on to the escape situation, what was your plan? And how did it come about that you set off alone without your wife?

We had heard this on the radio and the decisive factor was this announcement by the GDR lawyers Vogel and Gysi. I [sagte] to my brother: We’re leaving tomorrow morning at 5 a.m. in my Trabi. He had already ordered the tickets for the train to Hungary and a visa and we decided without further ado that we would drive there in our car and go straight to the embassy. We took Vogel up on his suggestion. And the plan was: we get registered, take up the offer [hin], leave the embassy again, go for a beer in the evening at U Fleků, the famous beer pub in Prague, eat some Bohemian dumplings, drive home and get back to our wives shortly before midnight. That was the plan. And then things turn out differently than you think. We drove along in the Trabi and arrive at the border in Zinnwald. At the border: nobody. No customs officer, no car, no one at all. So I drove slower than walking pace and suddenly we went through the light barrier. A siren immediately went off and police and the military came from everywhere and we were taken into a garage together with our car [hineingeführt]. Our car was taken apart. We were questioned individually, but we had already prepared ourselves. We were on our way to the Giant Mountains to find our next winter vacation spot [zu finden]. We didn’t have any documents or city maps in the car, [wir hatten] but we had already thought that this was exactly what they were looking for. And in the end they let us drive on. And then we drove into Prague and, because we had always followed it on Deutschlandfunk radio, parked our car three kilometers away in a side street and then took a cab. We took the cab to the embassy and spoke wonderful German with the cab driver. And then, as we were driving up the alley leading to the embassy, we said: Stop, we want to get out here. The cab driver didn’t react at all and just drove on. Stop! Stop! We want to get out here! He drove us right up to the door upstairs. And then we found out later that the cab drivers had been instructed by the Czech Department of the Interior that they all had to drive right up to the door so that the Stasi could shoot their films. So that they could photograph who was going to the embassy, who was getting out of the taxi, and then they’d already have them in the photo. Then we got out with our bags. Two gentlemen here and two gentlemen there with umbrellas and newspapers under their arms. It couldn’t be more classic. And then we said to ourselves: So, go to the door here and knock there [ist sinnlos], then you’ll be taken away first, you won’t stand a chance. So we walked around the back of this famous path, where we saw that the back of this famous fence was also occupied by the military and police. That’s why we continued straight up and [in] the forest and finally went over the wall and then into the embassy. And here I have to say one thing: that moment when we stood on the wall and felt the barbed wire between our legs. [hatten]one foot was on the other side and the other foot on this side and in the middle was the barbed wire, it was such an incredibly symbolic image. If you bend your knees now, it hurts. So make up your mind now. Do I jump back and pretend nothing happened? Or do I jump into the cold water and into the unknown? We ended up in an embassy compound, where we were arrested, lined up against the wall and patted down. And I still remember that horrible feeling of really having been caught at the last moment. But then it turned out that the American who had arrested us there wasn’t an American at all, but a man from Prague who worked for the American embassy. When we ran in there, he shouted ‘stoj! And we thought it was the Russian embassy, so of course we would have had zero chance. But then it turned out that he was from Prague and was working for the Americans. Oh man, how happy we were at that moment. He also made sure that we were able to get out through the back door. And then he waited and watched until the Czech police wanted to pull someone down from the fence again and then he opened his gate, we got out and then it went really quickly. The feeling when we were above the fence and slid down the inside, that’s… I still have goose bumps. […] And we got a Coke in there, it was the best Coke I’ve ever had.

[Zu der humanitären Situation in der bundesdeutschen Botschaft in Prag]

The nights got incredibly cold. There was frost on the ground and some people were outside [geschlafen]. Luckily, we were still on the steps [Platz gefunden]. We lay on a step and had organized big bags of semmel, [in diese] we crawled into them like sleeping bags. And spent the night in them. […] And then we were told that there was a risk of epidemics because more and more people were coming and we only had two toilet blocks. So people actually queued up to pee once and waited for three quarters of an hour.

How did you feel at the moment when Genscher's famous words were spoken? You didn't want to leave the country straight away?

The moment he said the words, we were of course all so happy. It was incredible. Because there was a green light somewhere in the overall political development. And that was incredibly nice. No matter what the embassy in Warsaw did, no matter what the embassy in Budapest did. The embassy in Prague had officially given the green light. And then the two of us, my brother next to me, were jumping in the air, romping around with everyone. And all of a sudden, [das] I remember you noticed how the lump in your throat got bigger and bigger. [Genscher] first said ‘your departure’ and then couldn’t finish the sentence. And then he took a quick breath and said: ‘The first train leaves in an hour. And then panic broke out. At first the crowds were still cheering like crazy, everyone was happy. […] And then Genscher said that the first train would be leaving in an hour. We weren’t used to that in the East, that something like that could be organized so quickly. And from then on, panic broke out. No film report shows what happened next [geschah]. Everyone ran off, they quickly grabbed their jackets and purses from somewhere, [sind] to the door [gelaufen] and the buses were already waiting outside. Everyone wanted to be the first on the first bus, everyone wanted to be on the first train, to travel by train at all. Then we got the feeling, yes, what about us? And while the crowds were still celebrating under the balcony, dancing and cheering, I said to my brother: “You stay here, I’m going to Genscher now. I actually ran off, ran up the stairs and went straight to him. His security people couldn’t react that quickly. I fell into his arms, grabbed his upper arm so that nobody could get in the way on either side and [sagte]: Mr. Genscher, I have a question. He looked at me and I have to say that at that moment, when everyone’s hair was standing on end, [agierte] Genscher was absolutely calm. Even Seiters from the Foreign Office, who was there at the time, was so calm [agiert], so calm… it was so good. You realized that you could somehow trust these people. They radiated a certain security, that was great. And then I said: my wife is six months pregnant, she stayed at home and so did our three-year-old son, what should I do? I’ve wanted this for years, now you say the train has stopped, get on board. And Genscher said to me: “Trust the Federal Government, we’ll take care of your case too. You are registered with us and trust us, come on board. And then I said to him: “Mr. Genscher, I’ve forgotten what trust means. To be honest, I’m afraid for my young, small family, my pregnant wife and my little son, that the Stasi will take revenge on my family in some way. I wanted to rule that out. And then more and more people joined [dazu kamen]. We then got together. Initially there were about a hundred people still there, many people spoke of 150 that evening. And then we decided not to go and basically stayed at the embassy. […] Five minutes after the last bus left [abgefahren ist], we were told to leave the embassy. There, I have to say, we got to know solidarity. We, now 72 people, said we’d stick together now. That’s where we realized what a difference it made. We then negotiated with the GDR embassy and the Czech embassy during the night. And we achieved a verbal exemption from punishment for us, we had nothing in writing. And early in the morning, I think around five, we had to go into the courtyard and [wurden] were briefed again. That day, within 24 hours, we had to enter Zinnwald, a very specific border crossing. And that’s basically where we were allowed to enter again. We left the embassy, [sind] to our Trabi [gegangen], which still had all four wheels, and drove back. On the way back, we heard on Deutschlandfunk radio that the 72 people who had left the embassy for the GDR would be allowed to leave for West Germany within the next 14 days. We stopped there at that moment and did a happy dance at the crossroads.