contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

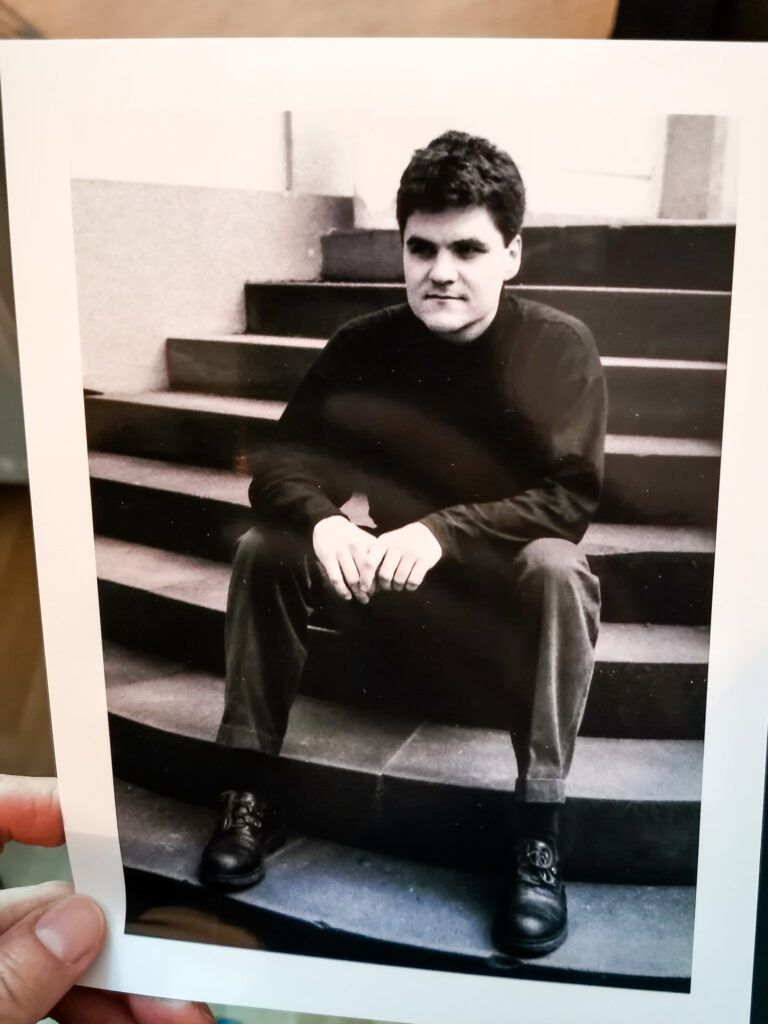

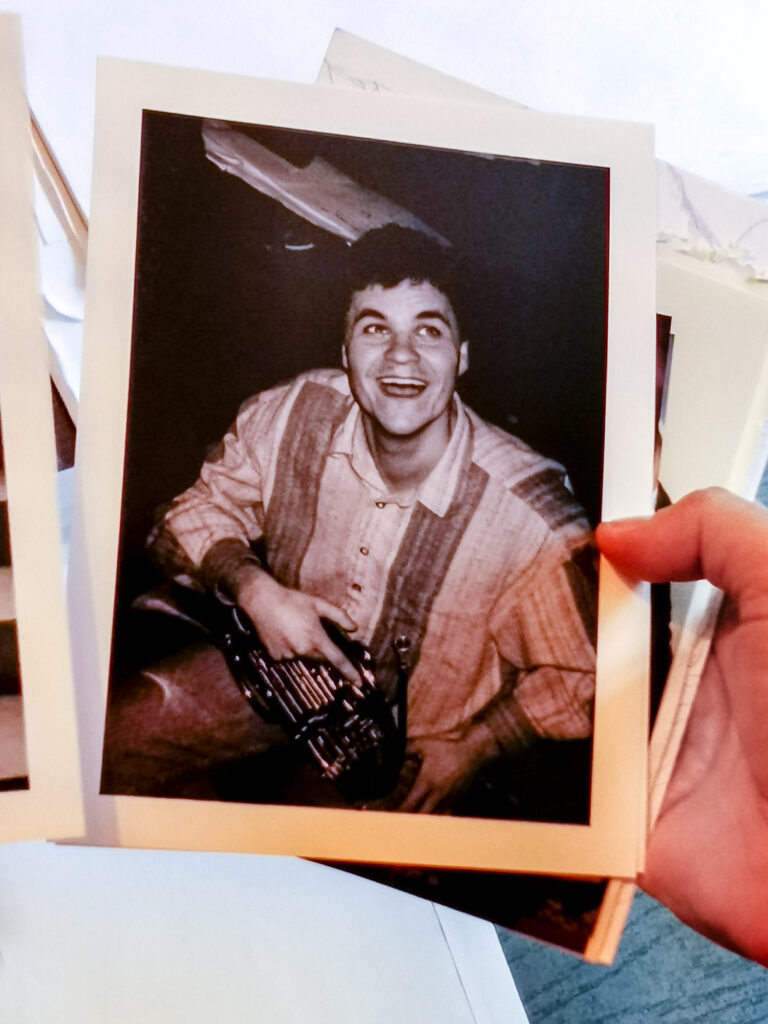

Markus Rindt

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Markus Rindt was born in Magdeburg in 1967 into a musical family that had a significant influence on his personal career. Encouraged early on as a child, he attended the special school for music in Dresden and was later admitted to study music. Even as a child, he harbored thoughts of escaping and declared his escape from the GDR to be a long-term goal. His oppositional stance was reinforced by friends and fellow students. He was almost exmatriculated for one of his critical actions. In 1989, the 20-year-old and his girlfriend at the time decided to try to escape via the Danube to Serbia or the border river Tisza between Slovakia and Hungary. However, he promised his father that he would first try to leave the country via the German embassy in Prague. After resting for two days on the forecourt due to the overcrowded embassy, they were allowed to leave and settled in Cologne with his girlfriend’s parents. There he was able to continue his studies and accepted international gigs that took him all over the world.

Following an assignment to Dresden in 1993, he returned to the East and settled in Brandenburg an der Havel for the long term. He still lives there with his family and works in Dresden as artistic director of the Dresden Symphony Orchestra.

Why did you leave the GDR back then, what was your personal motivation?

I had studied music in Dresden and my goal was always [es] [gewesen] to join an orchestra with which I could travel to the West. So preferably in a top orchestra like the Staatskapelle Dresden, the Dresden Philharmonic or the Berlin Staatskapelle. You often hear: as soon as you retire, you can travel the world. And when you hear that as a young person, it’s actually unbearable.

When I was 20, I had a friend whose parents stayed in the West on a visit. On special occasions, the GDR sometimes actually issued permits for visits. After a few days, we got a call to say they weren’t coming back. And we suddenly had a car in Radebeul near Dresden, a fantastic, beautiful and fully furnished apartment and a country house in the Ore Mountains. Towards the end of my studies, I also had a solo horn position at the Landesbühnen Sachsen in Radebeul and from a material point of view, there was really no reason to leave.

But my friend wanted to study art. She was then summoned by the rector of the university, who made it clear to her that if she didn’t work for the Stasi, she could forget about her studies. What’s more, her parents, who had fled at the time, had built up the Semper Opera House [und], for example, and worked in the museum sector; they really were experts in their field. And the Stasi didn’t take that lying down. They then summoned my girlfriend and her sister for daily interrogation. It was assumed that it wasn’t a normal escape. That went on for a while and that was enough for my girlfriend, [sie] applied to leave the country. Then [auch] it was clear to me: I didn’t end up in one of these top orchestras and I also had the impression that I wouldn’t be able to do it any time soon because I was always very excited during auditions [um freie Orchesterstellen]. And [dann] I thought to myself: then we’ll leave now.

You said that you had thoughts of escaping from childhood. Did you understand as a child that you only had limited options?

I understood [bereits] as a child that this was probably the case. My grandparents lived in Barneberg near Helmstedt. Barneberg was in the so-called exclusion zone, which you could only enter with a pass. You had to apply for one and we couldn’t just visit my grandparents because they lived at the real border. My grandfather often took me for a walk there and said: Look at the houses over there, they’re already in the West! And then he told me about his trips to Cologne or Bavaria. As a pensioner, he could travel. People often talked about their experiences in the West and described it [wie] as a land of milk and honey. The air [sei] was cleaner, the grass was greener and everything was better. [Es] wasn’t just about external things, but also [darum] how you could realize yourself. [Die Möglichkeit] travel the world, be able to read what you wanted or watch the films you wanted. Getting all the information you want.

And when you hear that from other adults as a child, it does something to you. For example, my aunt gave me a globe when I was in first grade. I spent hours studying it, turning it around and thinking about where I [would] go [if I] could. I was very interested in geography and just couldn’t imagine that this little country, [die DDR] was supposed to be everything. Of course I wanted to see the world.

You already mentioned that you had friends who were critical or oppositional. Did you also know people who were active in the New Forum, for example?

No, not personally. But I have to say that the music students [in der DDR] were relatively oppositional [eingestellt]. Many of these music students had parents who were active in the church. In this musical environment [herrschte] there was a critical spirit towards the state. As a result, students from other universities were told to be wary of these music students, who were opponents of the state. And it was also the case that we in the music studies department completely crashed the May Day parade [von 1988] as a protest action. Or the idea of disrupting the local elections [1989] by crossing out all the candidates.

I would say that it also has to do with the church background that many musicians had. And that’s why I would also say that the Monday demonstrations that emerged in Leipzig in the protected space of the church would not have been possible otherwise. The fact that people who were critical and wanted to make a difference were able to come together through these joint church services that offered this platform. That would not have been possible in any other space.

Let's move on to the escape, you already mentioned that your father had dropped you off in Mělník. Were there any contacts with the Czechoslovakian population and points of contact with other refugees in Prague?

When we arrived at [in Prag] and stood in front of a map of the city, completely at a loss, neither of us knew where to go. And there were lots of other [Ostdeutsche] people standing next to us. Neither of us dared to speak to the other. There was this feeling that this could be a provocation [der Stasi], that they could stand here and then pick us up. When Bavarian tourists showed us the way and we all walked across Charles Bridge, it was clear that everyone had the same goal. And then we stood in front of the [overcrowded] embassy and couldn’t get in. It was clear: you can’t stay here now, it’s no use, we’re standing outside the grounds. But we’ll wait here now. And of course there were many conversations. There were also moments of mistrust there. For example, I can remember very well that a photographer was taking pictures from the roof, certainly the press. And [als] he came down with his camera, they grabbed him, took the camera, opened it and tore out the film. So they were terrified that they would be [zu sehen] because he was taking pictures from the roof.

At some point we were told that the Czechs would also count the thousands of people [auf dem Botschaftsvorplatz] to [den Geflüchteten]. We were then able to move around freely. There were radios everywhere and we always listened to German radio. And then at some point the news came that everyone inside and outside the embassy could leave. There was a storm of enthusiasm and everyone threw their arms around each other’s necks. The Czech police had not only cordoned off this square, but a much larger area. I was even able to go to a restaurant with my girlfriend. There was a store where you could go in and I bought a bottle of Bohemian sparkling wine in case we made it. And of course there was also the need to go to the toilet somewhere. Some Czech families then made their apartments available and sometimes brought something to eat [und] to drink. We were no longer provided for directly by the embassy, but by the [local] people who lived there. And I thought that was super nice. You got the feeling that they definitely sympathized with us.

Were you afraid of being intercepted outside the embassy and had you thought in advance about what might happen if you got into such a situation?

We didn’t get there that easily. When we walked down from Charles Bridge, there were hundreds of people and a line of soldiers on the other side. It was the road leading up to the German embassy. And this line of soldiers with machine guns was impenetrable. There were a lot of people behind us, also determined to get to [in die Botschaft]. But it was actually impossible to get through [gewesen]. Then a father with his two children by the hand approached the soldiers and his mother followed, and the soldiers let him through. That was the signal for everyone else. But until then I didn’t know whether we would get through.

On the other hand, we had this back-up plan along the lines of: if we don’t make it here, that was the promise I had made to my father, then we will definitely go to Slovakia and swim across the river. I had dreamed of this adventure since I was a child. Not just thinking about how to do it, but lying in the evenings [wach] and thinking about it a lot as a teenager. So [einen] digging tunnels [zu] or building a raft [zu] [um] across the Baltic Sea. I thought about everything you can imagine. And it was clear from childhood that I would go on this adventure at some point. However, it has to be said that it is of course a thousand times better [war] that nothing happened to us, that it worked out so well and smoothly. A lot could really have happened, like my schoolmate who caught severe pneumonia while crossing the Danube.

How did things actually continue in Cologne? They also tried to find people work, which was probably not so easy as a young musician?

I was lucky enough to come across the horn professor Erich Penzel, [obwohl] I just wanted to borrow an instrument so that I could audition and get back into the orchestra. I was lent the instrument by a later fellow student, and then Professor Penzel said [dass] he would like to hear me play [würde]. And then I practiced outside in the city park for a few days and thought: He just wants to hear if I can play a bit. I didn’t realize at the time that he was such a luminary – the best horn teacher you could have, so to speak. He actually took me on in the middle of my academic year. I went on concert tours, I traveled a lot during that time, even abroad. [Alles]What I actually wanted to do, I was actually able to do incredibly well. As a musician, I’ve traveled the world a lot, come into contact with other cultures and that has paid off.