contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

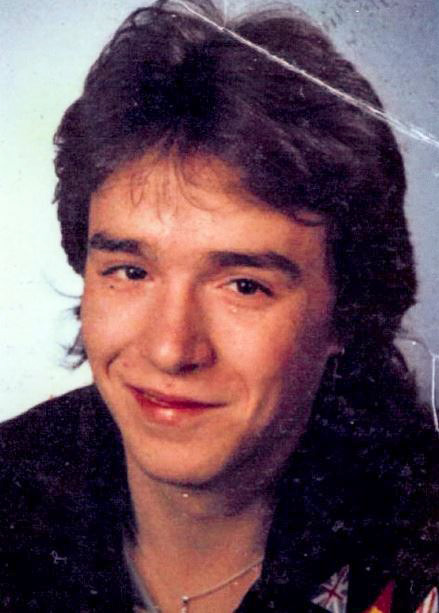

Jens Hase

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Jens Hase was born in Eisenach in 1970 and fled the GDR in 1989 to join his parents, who had already left for West Germany following an approved application to leave the country. At the age of 19, members of the State Security tried to put pressure on him to work as an unofficial collaborator. After his refusal, he suffered reprisals at work and his apartment was secretly bugged. When he saw the broadcast of the occupation of the embassy in Prague on West German television, he decided to flee that very night. At the embassy, he helped other refugees to get over the fence and into the embassy. He now lives with his wife in Günzburg, Bavaria, and regularly appears as a contemporary witness in schools.

What motivated you to want to leave the GDR?

Yes, I mean, that’s how many lives or biographies were. In the beginning [eine] I had a happy childhood in the GDR, until obstacles were put in my way when it came to secondary school. And when my parents fell seriously ill at the end of the 1980s and the doctors or our family doctor said that my father had relatively little chance of survival in the GDR, we applied to leave the country, but only my parents were granted permission. They were almost thrown out of the GDR within a very short time [wurden] and I had to stay behind alone at the age of 19. I had no idea about life, was afraid of life, afraid of being alone. And then I had my first thoughts of fleeing via Hungary, but I wasn’t granted a visa. And then came Prague. I always secretly watched West German television and then saw the pictures from Prague and that was the quick decision to flee.

How did you finally arrive at [in der Botschaft]?

So I had made various plans in Prague. I saw a newspaper kiosk and bought felt-tip pens and drew the German flag in the palm of my hand. The plan in my head was: Prague is a tourist city and if I hear people speaking German somewhere with an accent I don’t recognize, where I think they might be Bavarian or something else, I’ll secretly show them this flag in my hand. And then they know what I want and help me. But I didn’t meet anyone who spoke German and it was already late in the evening. And then I decided to go back to the main station and go home. I often wavered between staying and going.

And on the way to the main station you pass Wenzelplatz and there was a lonely cab. I still remember it today, it was an old Volga and I was frozen through, overtired and got into the car. I still remember the moment, because it was just warm in the [Taxi]. There was finally something warm around me again and I could sit softly. And then I showed the cab driver the German flag I had in my hand and he completely lost it. He shouted at me to get out and I didn’t want to get out. Once I was in there and [hatte] I lost hope and I kept saying ‘please, please’ and started crying. I was exhausted and he said he couldn’t do it. It’s a risk for him if he takes me there. And then I took out my wallet, put all the cash I had on the dashboard, my watch down, my necklace, it was all worthless really. But I put everything on the dashboard [gelegt] and kept saying ‘please, please’ [gesagt] and then he folded and said okay, he can’t drive me to the door, but at least to the neighborhood. I was so relieved and when we crossed the Vltava, I thought my God, I would never have thought of going to the other side [zu gehen]. I kept looking in the city center and then, the closer we got, I noticed more and more Wartburgs and Trabants with GDR license plates. Then I got annoyed with myself for not paying attention to things like that. That it didn’t even occur to me that you could see signs somewhere.

Yes, and then he let me out and then there was a nice scene. He just drove me to the area as we had agreed and then explained the way to me, left, right, straight ahead, I’d already forgotten and I walked, I’ll find it. Of course I didn’t find it, I was already behind Prague Castle again. It was such a cold night with drizzle, the asphalt was soaking wet and the parked cars and lanterns were flickering, just like in a movie. It was like a movie set and I saw three guys walking on the other side of the street, but I only saw the silhouettes. It was almost dark and I called over: German? Yes. Where are you going? But I didn’t trust them, so I called [fragte ich]: Where are you going? No, you say that first, no, you say that and that went round and round three or four times. And I was afraid that they might be Stasi people catching people. But I was so exhausted, I told [mir] the opportunity was good and said: Yes, I want to go to the embassy. Yes, we’re looking for [sie] too. And then I joined them.

And then I was no longer alone. Although I was always suspicious, I didn’t know where they were taking me. It could have been [dass] that they were taking me to the nearest police station. And there was an older man there, he had a stiff leg, there were two young guys my age and an older guy, I don’t know what kind of relationship they had with each other. And he was very slow. And that weighed on me again. I wanted to make progress and being slowed down so close to the finish line was bad for me. And we had to keep taking breaks and that was also one of the funny moments: We were sitting at one of those gates, leaning back on the cobblestones, and one of the young guys stopped. We were talking quietly and he looked up at the world history and then he said: I think I’m crazy. And then I look up and right above me is the sign ‘Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany’.

We were sitting right in front of this door and I remember jumping up and being confused at first because there was a fence on TV, there was a forest [zu sehen]. And there was neither a forest nor a fence. And then I started running, instinctively uphill, and there was a police station opposite. Today I think it’s an Italian cultural building. But I didn’t know that and when I started running – the older man said, slow down, we mustn’t attract attention – I blew all my fuses. And then the door opened and [es] armed Czech soldiers in uniform came out and shouted stop. And then I ran off. I was so scared, so close to the finish line, and I didn’t even notice the other three. I was in a trance, running for my life, expecting them to shoot the whole time. I also thought about whether it would hurt if I was hit by a bullet like that. And then I turned left and that was exactly the way to the embassy fence.

Were there fears in the embassy garden that members of the Stasi were walking around there? Were there any encounters, was the danger discussed?

So everyone was suspicious of everyone else. You could always tell. I experienced two things where I’m definitely sure it was the Stasi. We were always at the fence, there was always television there and I wanted to get close to the cameras in the hope that my parents in the West might see that I was there and that I was doing well. That was the plan behind it. I stood at the fence, looked at the cameras and then all the other refugees suddenly turned away and covered their faces. And I didn’t even know why. [Frage]What’s going on? Then one of them says to me, look. There was a photographer outside and he was wearing very distinctive GDR clothes and had a Praktika, a typical GDR camera. And then they all thought he was a Stasi man. But he didn’t realize it and someone called him over. Says: Hey you, I need you for a minute, can you come here? And then he came up to the fence and then five or six arms grabbed him through the fence. I’ve never seen a person being beaten through the fence before, he couldn’t get out. They really beat him up through the fence.

And the second situation was in the tent further down, where I once witnessed tumultuous scenes. I didn’t hear it myself, but I noticed it because there were more and more people around and security came and took an injured man out of the tent. And then I asked what was going on. And it was probably like this, someone recognized him as his interrogator and insisted on it and he probably denied it, said: No, that’s not me, you’ve got me mixed up. And then it must have gotten out of hand and someone must have said: We’ll kill him now, we’ll bury him, nobody will find him anyway. And then the mob got on top of him. I think they would have beaten him to death. The ambassador and [die] security got in between, they got him out injured, the hospital was right opposite. So those were two situations. But to be honest, I was 19, I hated people too, everything was going through my head. The separation from my parents and, and, and. That’s why I didn’t care what they did to me, because I thought they didn’t deserve it any other way. So the hatred towards these people was already great.

It would be particularly interesting to know what the situation was like after Genscher's announcement, when it became clear that everyone was coming out. Were there cheers and did everyone go straight onto the buses or were there a few hours in between? And if so, what do you do in this very euphoric mood?

When he said that the trains would run every two hours and across the territory of the GDR, the mood immediately soured, for me too. I said no, then I’ll stay here. Topic already over again. So from the cheering in principle, from the high-life all the way down again. And he realized that and said that he had once left Halle himself and that he knows how we feel. And he also said that he would guarantee that nothing would happen to us and that people from his office would be on every train. That reassured us, but the fear was there. And when we went to those buses – and I don’t just mean German history, but also European history – when we went out to those buses, which were further down, there was something that I have never forgotten to this day. There were thousands of Czechs standing to the left and right, who actually had exactly the same situation as we did in our country. And they stood [dort] and applauded us. I remember walking down there, my hair was standing on end the whole time and I could already feel that something was happening here. It was a crazy scene.

Was there a change in solidarity after the borders were open?

A very clear yes. November 9 was the change in solidarity. When the Wall fell, I cheered, I celebrated, I thought it was so great, I never thought it was possible. And then days or weeks later, things started to happen. When the first East Germans came, and it wasn’t just those who wanted to work, I have to be honest, there were also a lot of people who thought I was going to make myself at home here and the roast goats would come. I was actually ashamed of some of them. In the company where I worked, I was the first East German and then suddenly lots of people came. And I know that at the beginning my boss said that for every East German, GDR national, they would give you a bonus of 50 marks. But I never did that because the risk was too great that I would bring someone with me who would then be held against me. And then there really were a lot of people who attracted negative attention. Then I immediately realized that the people who had patted me on the back weeks before and said it was great what you had done were the ones who then said: You stupid Ossi, you’re only here for the money anyway. It really hurt me back then, I have to say.

That’s when my eyewitness work actually started. In Kirchheim, which is not far from me, I went to a village pub in the evening. The first person I met here was an Italian. That was the first friend I had. And I went to this pub with him. And there were three native Bavarians sitting at the table, I’ll never forget them, with their caps and beards on top at the regulars’ table. And then I heard: Stupid Ossis, they won’t get a cent from me, not a penny, it was still pennies, they’ll get from me. And that didn’t really affect me any more, but it still annoyed me. And then I took my beer, my buddy wanted to hold me down, said they don’t do that here, I said I didn’t care, sat down and then I told them my story. And I said: You know, just a few weeks ago you said our brothers and sisters in the GDR. Maybe we need a bit of solidarity, a bit of help, a bit of money and your mood is immediately gone. Then the three old men left, I saw them a lot afterwards. I don’t know if they’re still alive now, but they always greeted me when I drove through Kirchheim. They probably haven’t forgotten me. I think those were the first three people I turned around. And that was the reason why I said, now I talk to everyone. And anyone who makes fun of me because of my background, I’m going to talk to them. And that’s what I did.

Before the escape or after the escape, were there debates among friends and family as to whether this escape movement in the GDR was the right way or whether everyone should have gone to the New Forum? Was there a moral discussion on the subject?

No, I didn’t realize that here. Many people say we wrote German history with our escape from Prague. But I didn’t go to Prague because I wanted to write history, I wanted to see my parents. I never thought about the fact that we were writing history. We did that unconsciously and that’s why I’m sometimes invited to events today, but then I meet people who say: you’re another one who ran away, you didn’t even fight for the cause in the GDR. That sometimes makes me feel a bit bad. I have to say that. But nobody could have known. And today I regret [das] of course, I would have liked to have experienced the time of upheaval in the GDR. What it was like there must have been exciting too. But I just followed it from the West. But today I sometimes feel bad because I’m often really attacked by people, especially on social media. I’ve even received death threats if I don’t stop talking so badly about the GDR… But I also say it again and again at schools, I tell pupils: the story you hear is my personal story. Not everyone thought the GDR was bad, that’s clear. But you can form a picture of whether it was a constitutional state or not based on my story.

You said that you travel to Prague regularly and that it is a very positive place [für Sie]. When was the first time you were back in Prague and at the embassy after your escape?

September 29, 2014, the day before the 25th anniversary. I never went back because I didn’t think about the fact that the place could mean something to me. [Ich] Then I went there and thought: Yes well, I’ll go there, go in and have a look. And the gate opened, I walked in and couldn’t breathe. I never thought it would be so hard for me. I was in tears because the moment the gate opened and I saw those cobblestones, it was like a puzzle game where a few pieces were missing and suddenly the pieces were there in my head. Then I saw the people walking again and I knew immediately, even though I hadn’t been there for 25 years, where my step was. I came in there, turned right, went up the stairwell and there was my staircase. It was suddenly there again. And that’s when I realized that it’s still an important place for me today. And when I go there, I always feel at home. Every time I come to this Genscher balcony, as it’s now called, it brings tears to my eyes. Because I always have this bliss, [so] I think you could call it, in my head.