contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

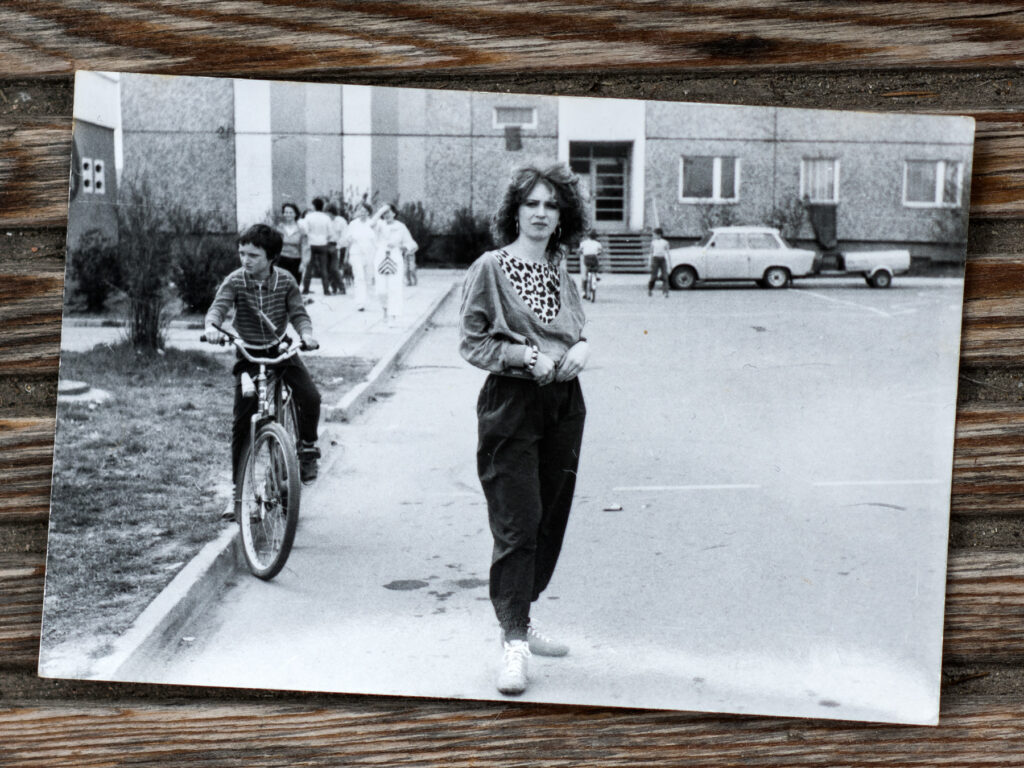

Ina Karsten

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Why did you leave the GDR back then, what were your motives?

I was 18, had just finished my apprenticeship, trained as a hairdresser in the GDR and many of my friends had left the GDR. My boyfriend did too, and there was a sense of new beginnings. First of all, you’re young, 18, you want to experience something and on the other hand [herrschte] there was also the upheaval. You wanted to travel and do something [erleben]. And then we went to Hungary in the summer with my friends. We went there with a few girls and got to know some West Germans and thought with them that maybe we could flee via Hungary. We also looked into it by car and simply drove there [um] to [gucken]. But in the end we didn’t dare. I then came back and worked as a hairdresser and had a friend, [deren] a friend who had already left for the West. And we kept thinking back and forth about what we would do if the opportunity arose, then we would flee. And that evening, [an dem] Genscher said [hat] that people would be allowed out of the embassy, we said: Okay, if some people go back into the embassy, then we’ll be there too.

How was flight discussed in your environment in the GDR? Not only about 'Republikflüchtlinge', but also about this first group that was in the Prague embassy.

We thought it was cool when we were 18 that some people were so brave. However, [von] none of my friends from back then escaped via the embassy. You had to have a certain amount of courage [zu] and they wouldn’t have had it. We drove back from Hungary, we wouldn’t have dared to walk over there. I don’t think we talked about it that much. It wasn’t talked about that much. I was always a bit of a rebel [gewesen] and at some point I simply took down a picture of Erich Honecker in the hairdressing salon and turned it around; it was hanging in the back of our common room. [Es] There was a certain unrest in the city. The city was always a bit restless. But it’s not like we sat together and talked about something like that. We didn’t. But it was always [erzählt]: Oh man, he’s gone now too and he’s already gone and he’s gone, that’s how it was talked about. But not necessarily how and in such detail. At 18, that wasn’t really our topic.

What did you actually expect for yourself when you fled to West Germany, what hopes and expectations did you have?

I was 18, had just finished my hairdressing apprenticeship and thought, what does the world cost? I can’t hang around Lobeda all the time. I grew up in Lobeda, if you look at it, [das] is such a new development. It was a lovely childhood with all my friends in and around the house. We always did a lot. But at some point I thought, no, there must be more, there can’t be. And [du] you can’t just go to Berlin every now and then. And I just wanted to see more of the world and see what else was out there. It was such a curious spirit of discovery, [welchen] other 18-year-olds [auch haben], to travel first. That was also the case. I was done, I wanted something nice and cool for myself.

When you arrived at the embassy, did you already have a kind of feeling of freedom, did you have confidence in the Federal Republic or in the representatives of the Federal Republic on site?

I had that. I didn’t have a feeling of freedom because it was so cramped, you couldn’t breathe. It was really cramped and I also understood why they said that no one else [in die Botschaft] was allowed in. I just couldn’t understand why I wasn’t allowed in now. I had come all this way because I wanted to and then accepted standing like that. So I squeezed in with them. And that was, you can imagine, like the Love Parade [stattfindet]. When everything is full, you can’t get in or out. It was really packed. You just sat on the floor on your bag somewhere. The weather was fine, I didn’t freeze, I can’t remember that. But upwards [hin war] the sky was open. That was the feeling of freedom up there [hin], but still tightness, something had to happen. And I had confidence, yes, I did. I don’t know why. As I said, we had met nice people in Hungary who said do it, come and that’s cool. And I had heard that on the radio and somehow trusted it.

Was there a moment of 'we are doing our part to bring down the GDR' when you left the country? Did it feel like a historic moment, on the train for example?

So for me, I was a young person and now I’m showing them that they can’t keep young people like this. That something has to happen. We always had civics lessons and knew that we only had to say this and that to get certain grades and we behaved in a certain way. Then there was a kink that I wasn’t supposed to get the hairdressing training I actually wanted. And that’s why I looked around to see what else I could learn. But that didn’t happen. For example, I was never meant to be able to do my A-levels. I then trained as a hairdresser. In the East, I would have resigned myself to that, but then I thought: you can’t do that for the rest of your life and be a slave and they treat you like that here… Then something had to happen and [ich] also considered doing my master’s degree in the West and things that wouldn’t have been possible before. And I’m also angry with the GDR for suggesting that. Once you’ve learned a profession, you’re supposed to do it until you retire. I couldn’t imagine doing that at 18, it wasn’t possible at all.

When you look back on the decision now, how do you assess this moment for yourself in retrospect?

I had been done with it for a while. I made the ad hoc decision to ride the next day, but it matured as a result of many, many things that happened beforehand. It was like a little plant that took root and became a tree and then at some point there was a fruit and it was ready. Then you sprouted. And so it was logical. It was a conclusion from this whole thing, there was no turning back for me. Something should have been different beforehand. You were actually [nur] looking for the moment when a gap like that would open up.