contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

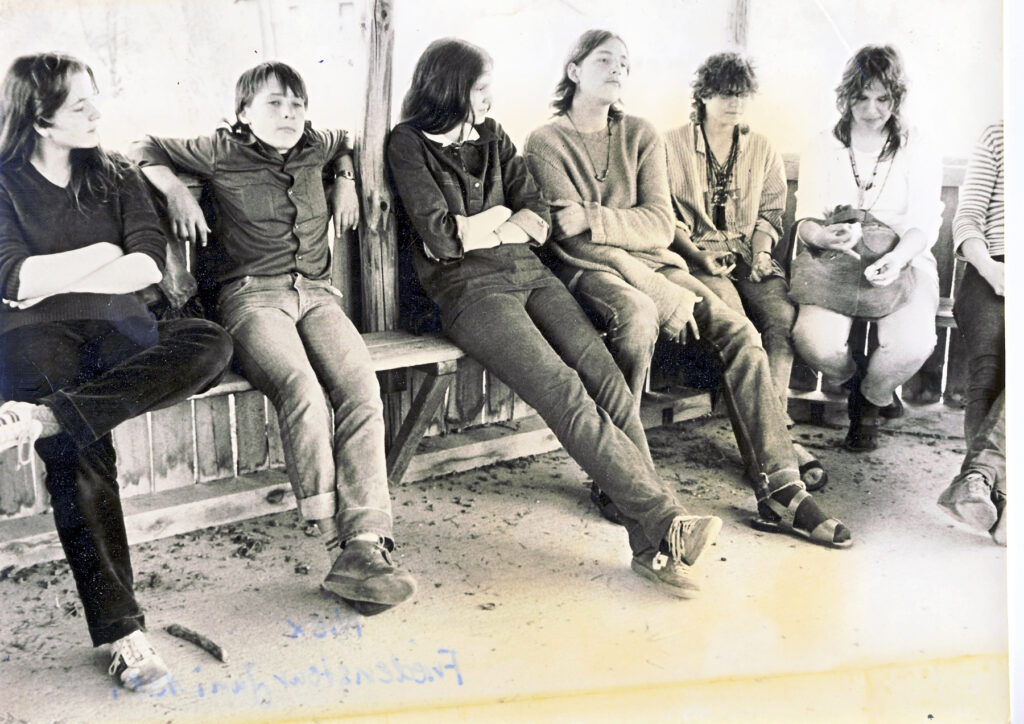

Heiko Strohmann

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Why did you flee to Prague?

In the eyes of my parents, I drifted further and further into a counter-revolutionary direction. [Ich] I was clearly told after leaving school that I wasn’t allowed to study and that was the punk moment for me [gewesen], when I said that this was the end. At the age of 19, after leaving school, I was a failed existence and from then on I more or less only had the thought of starting a new life somewhere because it wasn’t possible in the GDR. And since a revolution or the downfall of socialism was unimaginable at the time in 1987, 1988, the only option for me was to flee to West Germany. And I prepared myself for that and looked into it, and then it was just a fortunate circumstance with Prague. Hungary was actually on the cards, but I couldn’t get a visa for Hungary and Czechoslovakia was better.

Did you have any arguments with your parents when they realized that you were straying from the line?

Yes, there were massive arguments with my parents. That was actually the worst problem. The worst problem wasn’t that they called me names, that I was a failure or that I was disappointing or anything like that, but that my father didn’t fight for me. He didn’t stand up for me. I had an uncle who was even more loyal than my parents, my mother’s brother. And he was in customs, [hatte] also a fairly high-ranking position, who then took me to family celebrations [nicht reingelassen hat]. If I wanted to go to a family party, I wasn’t allowed in. He opened the door and said: You’re not welcome here, you’re a pest.

To be more specific, was the reason that you were not allowed to study really the decisive factor in your decision to flee? Were there other reasons that played a role?

No, it wasn’t about studying. That wasn’t the priority at all, but at 17, 18, 19 I realized that if you didn’t conform, you would have massive problems. In a conversation with my principal at the school where I did my A-levels, he told me very clearly: we don’t really have high hopes for you, but you can prove yourself in production. I could have gone into the shipyard and worked there as a locksmith or as a worker, and then at some point I could have studied at night to become an engineer or something like that. But I knew that I would always come up against limits that were not intellectual, but always political. And I would always have had to achieve more, be better and better, cower more and more, and I didn’t want that. And when you realize how sick the system is, you don’t want to do any more. So I knew that this system was sick and I could see that it would collapse economically sooner or later.

My father was one of the chief economists in the GDR, he worked in shipbuilding, it was Rostock, it was all shipbuilding. And he knew a lot about the financial and economic situation in the GDR. He got drunk and said at a birthday party in 1983 that they were getting brave, the lights would go out here in ’92 at the latest anyway, then we’d be bankrupt. And that’s how I knew I had no prospects, that became relatively clear to me. With or without a degree. I could look for a niche, which I did, I became a showman and the showman’s profession was the only one in the GDR that was still purely private. There was no private sector except [der] showmanship and I was free to do that, so I had my peace and quiet. It was also financially attractive and I wasn’t part of any system. But it was just a transitional phase and then the question was, what would happen in this country? Or do I have the chance to leave?

After my first meetings with these people, I actually ruled out the possibility that the civil rights movement would win at some point. They were all nice and idealistic, but unworldly and divided. The only thing that united them was their opposition to the SED. But after the fall of communism, you could see relatively quickly how things had fallen apart. And then you still have the people, who sometimes have a different opinion than civil rights activists. The GDR would still exist today if it hadn’t collapsed economically, so it didn’t fail ideologically. It failed economically. And this realization prompted me to simply sit down and wait. That happened relatively quickly in ’89.

Were you aware before or during your escape that you might not see your friends again?

Yes, I was aware of it, but I had no family and I had no friends. From the moment I realized, and that was in ’87, that my term here in this country was manageable, I stayed away from friends. Also to protect them. I had an apartment and then I disappeared overnight. My brother took me to Prague because he had to take the car back. That’s how it became known and then my family emptied my apartment and the state security came days later. Under normal circumstances, you assumed that when you left, state security would come the next day and interrogate everyone around you. And then it’s simply better if you don’t have any friends. I stuck to that and I didn’t really care about family.

How was this first group of refugees, who spent several weeks in the embassy, perceived in the GDR? What was the mood among the population?

Great, courageous, but pretty crazy people. That’s how you can sum it up. […] It was great what they took on without having the slightest chance, as we thought, of achieving their goal. We assumed at the time that they would leave them there to rot. But I thought it was great. That there are people who are either so desperate or so brave. But pretty crazy to do that. And especially with children.[…] I’ve always stuck to it, everyone has to make the decision for themselves. I thought they were brave back then, the people. But pretty crazy to do it.

Was this opinion a consensus among the population or were there voices that condemned it?

I do believe that the majority of the normal population perceived what I was saying. I didn’t even hear people in positions of power saying that we are such a great country and how can they leave this paradise of workers and things like that. There was nothing like that. The only thing was, and some of them were even people who weren’t politically left-wing at all, i.e. who were actually very critical of the state, who said: But with the children, you can’t expect them to do that, and I mean, it’s all crap here, but so bad [geht es uns nicht]. We have food, we can go on vacation to the Baltic Sea every now and then or something. It’s not quite that bad after all. There was that. But that was more along the lines of [Kinderwohl]. Politically, I think there was a consensus. But nobody saw them as revolutionaries, they just said: Okay, if they’re that desperate, that’s brave, but crazy. Nobody could imagine that the GDR would collapse because of a few crazy people.