contemporary witnesses - to the individual pages

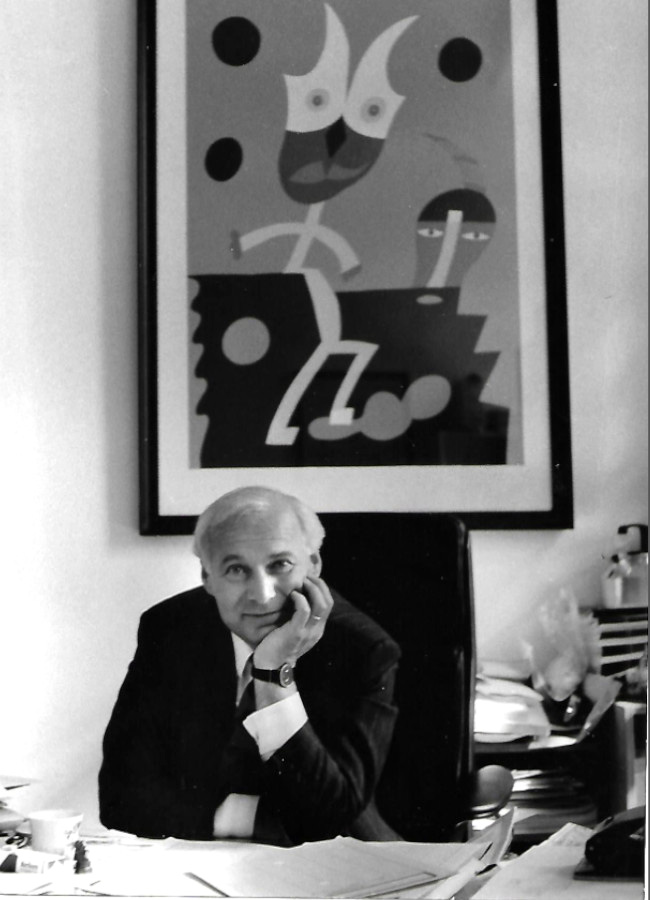

Hans-Joachim Weber

Foto: Manja Herrmann

Hans-Joachim Weber was born in Berlin in 1942 and, after attending school in 1958, began an apprenticeship with the Federal Railway and the German Armed Forces. In 1966, he was one of the first development workers (DED) and set up a school for metalworking professions in Tunisia. After 2 years, he returned and worked in public relations at Inter-Nationes for missions in Africa. From 1969, he was deployed in various countries in Africa until he was taken on in the Foreign Service in 1974. After various positions, he was transferred to the German Embassy in Prague in January 1989 at the request of Ambassador Hermann Huber. There he was responsible for the GDR citizens who came to see him. When more and more people sought refuge in the embassy from May 1989, Weber was also responsible for looking after them. On September 30, 1989, he accompanied the refugees on the first train to Hof. After the opening of the Berlin Wall and the inner-German border, he experienced the “Velvet Revolution” in Czechoslovakia.

After further stops in Copenhagen, Sarajevo and Berlin, he retired in 2009. Today, the former diplomat lives with his wife Hildburg in Bienenbüttel.

What did your everyday life at the embassy look like, what was your exact task?

GDR citizens came to the embassy almost every day. They snuck in because they were not officially allowed to visit the German embassy. If the front gate was open, then [sind] they got in. However, they always got in. They were rarely chased away by the militia who were opposite. At that time, the Federal Border Guard was still at the front of the door to ensure security at the embassy. And then they came in and said ‘we are GDR citizens’ and came to me. I was the first point of contact, unless there were 40-50 people a day, then the consul helped out, Mr. Rünger. But otherwise they waited in the corridor and I always took 45 minutes [genommen], did an interview, wrote all the things down. And they sometimes waited outside for half an hour, sometimes less if they [vorher] were already there. Some of them had already been there two or three times. And [da] the announcement was always: But we’re staying here, Mr. Weber. We were here two years ago, but we were always put off and told to come out and do something and that didn’t work out. We have acquaintances who were also here, they were in [den Botschaften in] Warsaw or in Budapest and they have now left for Germany. That meant fixing, we didn’t want that. I had to talk to them and make sure they didn’t stay.

You accompanied the first train. How did that feel for you? Did you have faith that everything would go well?

Ja, we had that trust. That was agreed. Genscher actually wanted to go on the first train. But the GDR turned that down. Then Genscher and his office manager said that Mr Kastrup, the political director in the Foreign Office, Consul Rünger, my superior, and Mr Weber would go with us. They would accompany the first train. The mood was good. The Stasi people came in, everyone laughed, made jokes and threw their money out the window. We knew that something would happen. If the GDR had promised something, they kept their word. They were more German than German. The mood was of course unbelievable when the first train arrived in Hof at 6 in the morning. But nobody was ever afraid. I walked through the train now and then and otherwise I sat in a compartment with a few people, the train was overcrowded. No, everything was fine. We never had the thought that things could go wrong or that they would put us on a siding or something like that.

When did you and your colleagues realize that larger numbers of refugees were now arriving?

We weren’t aware of that. We knew that they were coming every day. It started back in 1984, when there was already a mass refugee intake. […] Then it was quiet for years, but [es] there were people every day. People came in every day and said: Here we are. […] There were also days when nobody came and then 30, 40 came again. I think there was once a day when 100 came. I persuaded 90 to leave again, but ten stayed. But we didn’t know that it would go up like that. Nobody knew that, not even Genscher. Nobody knew that. Nobody knew that the borders would be open either. There was no plan B either.

But if you think about how this would continue for years, it wouldn't have worked for thousands of people to come to the embassy and leave together. Did you think about how it could continue?

No. If November hadn’t come, the last wave of emigration in November on the third/fourth of November and the opening of the Wall […], then it would have continued like this. Or the GDR would have had to close the border with Czechoslovakia, which it did for a few days. Then people would have just come through the bush. […] There were no plans, it would have continued. It would have continued like this until Erich came and said: I’ll turn off the light and that’s it. So, there were no plans at all. There was no idea either. We were surprised too.

Some contemporary witnesses have told us that they encountered Stasi members in the embassy. What can you say about that?

Yes, [das] that might happened as well. We didn’t know about the people who came over the fence. We took everyone’s personal details and they didn’t say: we’re from the Stasi. We knew that some were coming. Some came over the fence, registered their identity with a false identity and then ran off again the next day, went back over the fence and just wanted to listen to what was going on. They caught one of them, he was taking photos. They didn’t beat him up, but they beat him up. He had to take the film out and they pushed him to the side a little. One of them came and said: Mr. Weber, can I speak openly? I didn’t stay in the office with him, I went outside around the corner where no one could hear. And he was from the Stasi and said: I’m from the Stasi, here’s my ID. We then copied it. And I said: Well, what do we want to do, what do you want to do? Go back. He also wanted to leave the country. I said: you have to go back, we can’t leave you here, what are you doing here? He then went back again, nobody even noticed. I said: get in the back of the VW bus, I’ll drive you. I drove it out to the train station in Libeň or Holešovice and gave him the fare.

How did you experience the Velvet Revolution in the embassy?

Of course we did [beobachtet]. I wanted to go to Wenceslas Square on November 27, but we weren’t allowed to because we didn’t know what was going to happen there. But the [Samtene Revolution] went well. I was one of the first people to visit Havel two days later to say hello and offer him help. But Havel had always had good contacts with the embassy through Charter 77. We have always supported Charter 77, with money and photocopiers. We’ve always had a good relationship with them and maintained it.